-40%

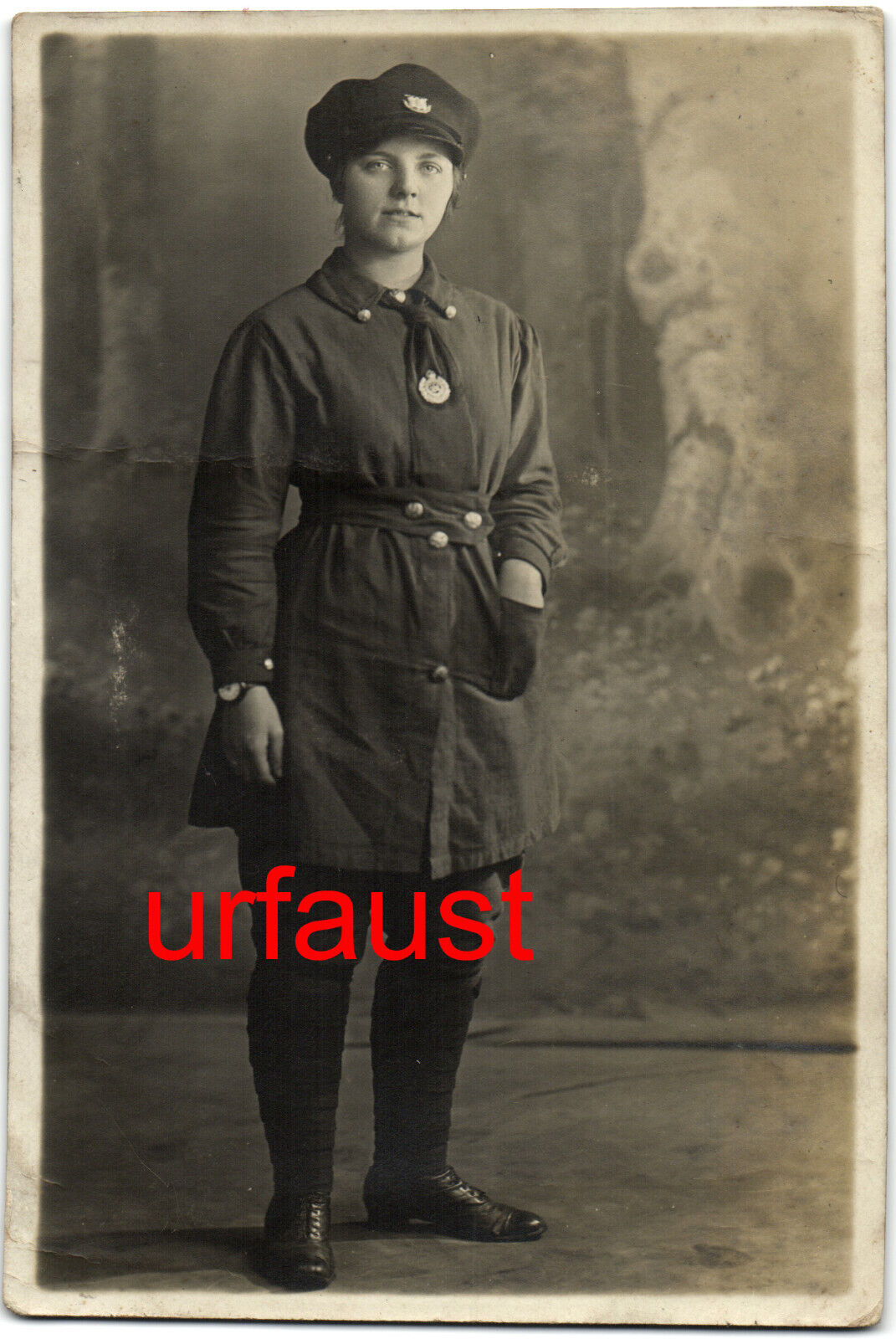

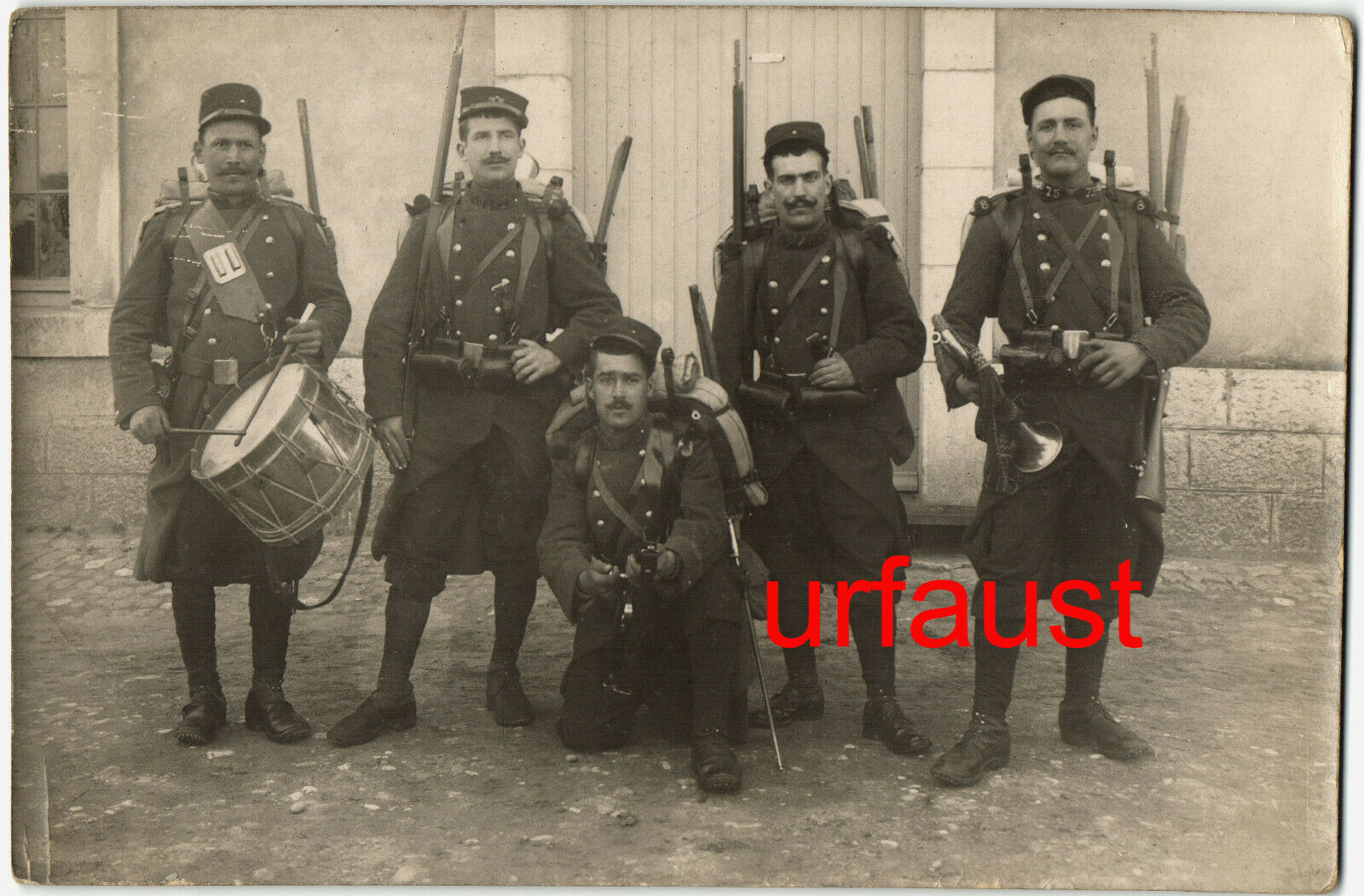

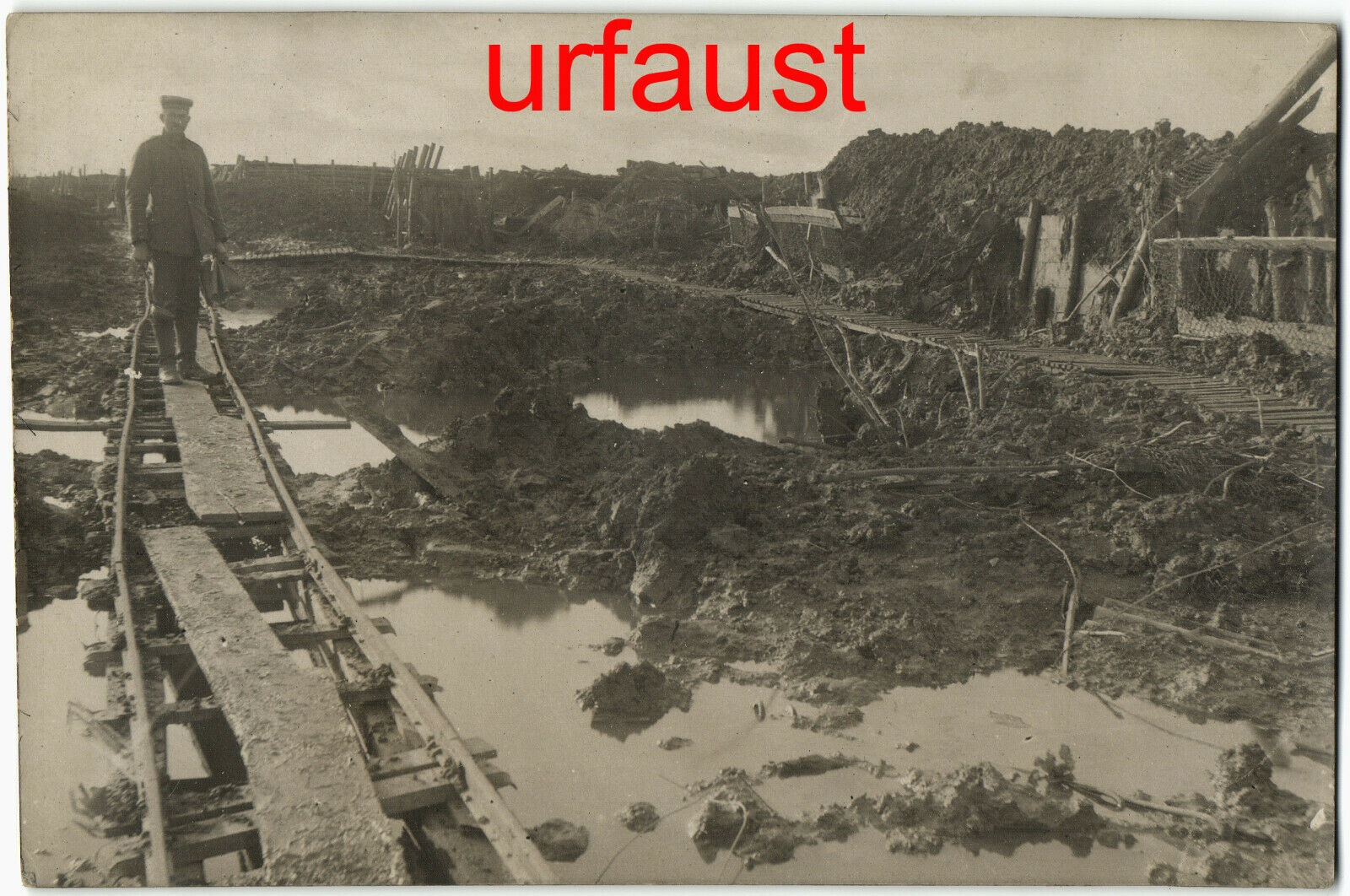

WW1 1915-18 Western front France Unknown location German troops Original S1353

$ 21.12

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

SearchVintage gelatin silver photo

detached from an album

sheet

Photographer:

unidentified

1916c

Size of the photo: 8,8x12 cm

Condition: Good (see scan)

The Western Front was the main theatre of war during World War I. Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne. Following the race to the sea, both sides dug in along a meandering line of fortified trenches, stretching from the North Sea to the Swiss frontier with France. This line remained essentially unchanged for most of the war.

Between 1915 and 1917 there were several major offensives along this front. The attacks employed massive artillery bombardments and massed infantry advances. However, a combination of entrenchments, machine gun nests, barbed wire, and artillery repeatedly inflicted severe casualties on the attackers and counter-attacking defenders. As a result, no significant advances were made. Among the most costly of these offensives were the Battle of Verdun, in 1916, with a combined 700,000 casualties (estimated), the Battle of the Somme, also in 1916, with more than a million casualties (estimated), and the Battle of Passchendaele, in 1917, with roughly 600,000 casualties (estimated).

In an effort to break the deadlock, this front saw the introduction of new military technology, including poison gas, aircraft and tanks. But it was only after the adoption of improved tactics that some degree of mobility was restored. The German army’s Spring Offensive of 1918 was made possible by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that marked the end of the conflict on the Eastern Front. Using the recently introduced infiltration tactics, the German armies advanced nearly 100 kilometres (60 miles) to the west, which marked the deepest advance by either side since 1914 and very nearly succeeded in forcing a breakthrough.

In spite of the generally stagnant nature of this front, this theatre would prove decisive. The inexorable advance of the Allied armies during the second half of 1918 persuaded the German commanders that defeat was inevitable, and the government was forced to sue for conditions of an armistice. The terms of peace were agreed upon with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

1914—German invasion of France and Belgium

At the outbreak of the First World War, the German army (consisting in the West of seven field armies) executed a modified version of the Schlieffen Plan, designed to quickly attack France through neutral Belgium before turning southwards to encircle the French army on the German border.[12] Belgium’s neutrality was guaranteed by Britain under the 1839 Treaty of London; this caused Britain to join the war at the expiration of its ultimatum at 11 pm GMT on 4 August. Armies under German generals Alexander von Kluck and Karl von Bülow attacked Belgium on 4 August 1914. Luxembourg had been occupied without opposition on 2 August. The first battle in Belgium was the Siege of Liège, which lasted from 5–16 August. Liège was well fortified and surprised the German army under von Bülow with its level of resistance. However, German heavy artillery was able to ruin the key forts within a few days.[13] Following the fall of Liège, most of the Belgian Army retreated to Antwerp and Namur, with the Belgian capital, Brussels, falling to the Germans on 20 August. Although the German army bypassed Antwerp, it remained a threat to their flank. Another siege followed at Namur, lasting from about 20–23 August.[14]

For their part, the French had five armies deployed on their borders. The pre-war French offensive plan, Plan XVII, was intended to capture Alsace-Lorraine following the outbreak of hostilities.[15] On 7 August the VII Corps attacked Alsace with its objectives being to capture Mulhouse and Colmar. The main offensive was launched on 14 August with 1st and 2nd Armies attacking toward Sarrebourg-Morhange in Lorraine.[16] In keeping with the Schlieffen Plan, the Germans withdrew slowly while inflicting severe losses upon the French. The French advanced the 3rd and 4th Armies toward the Saar River and attempted to capture Saarburg, attacking Briey and Neufchateau, before being driven back.[17] The French VII Corps captured Mulhouse after a brief engagement on 7 August, but German reserve forces engaged them in the Battle of Mulhouse and forced a French retreat.[18]

The German army swept through Belgium, executing civilians and razing villages. The application of “collective responsibility” against a civilian population further galvanised the allies, and newspapers condemned the German invasion and the army’s violence against civilians and property, together called the “Rape of Belgium”.[19] (A modern author uses the term only in the narrower sense of describing the war crimes committed by the German army during this period.[20]) After marching through Belgium, Luxembourg and the Ardennes, the German army advanced, in the latter half of August, into northern France where they met both the French army, under Joseph Joffre, and the initial six divisions of the British Expeditionary Force, under Sir John French. A series of engagements known as the Battle of the Frontiers ensued. Key battles included the Battle of Charleroi and the Battle of Mons. In the former battle the French 5th Army was almost destroyed by the German 2nd and 3rd Armies and the latter delayed the German advance by a day. A general Allied retreat followed, resulting in more clashes such as the Battle of Le Cateau, the Siege of Maubeuge and the Battle of St. Quentin (Guise).[21]

The German army came within 70 km (43 mi) of Paris, but at the First Battle of the Marne (6–12 September), French and British troops were able to force a German retreat by exploiting a gap which appeared between the 1st and 2nd Armies, ending the German advance into France.[22][23] The German army retreated north of the Aisne River and dug in there, establishing the beginnings of a static western front that was to last for the next three years. Following this German setback, the opposing forces tried to outflank each other in the Race for the Sea, and quickly extended their trench systems from the North Sea to the Swiss frontier.[24] The resulting German-occupied territory held 64% of France’s pig-iron production, 24% of its steel manufacturing and 40% of the total coal mining capacity, dealing a serious, but not crippling setback to French industry.[25]

On the Entente side, the final lines were occupied by the armies of the Allied countries, with each nation defending a part of the front. From the coast in the north, the primary forces were from Belgium, the British Empire and France. Following the Battle of the Yser in October, the Belgian forces controlled a 35 km length of Belgium’s Flanders territory along the coast, known as the Yser Front, along the Yser river and the Yperlee canal, from Nieuwpoort to Boesinghe.[26] Stationed to the south was the sector of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Here, from 19 October until 22 November, the German forces made their final breakthrough attempt of 1914 during the First Battle of Ypres. Heavy casualties were suffered on both sides but no breakthrough occurred.[27] After the battle Erich von Falkenhayn reasoned that it was no longer possible for Germany to win the war, and on 18 November 1914 he called for a diplomatic solution, but Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff disagreed.[28] By Christmas, the BEF guarded a continual line from the La Bassée Canal to south of St. Eloi in the Somme valley.[29] The greater part of the front, south to the border with Switzerland, was manned by French forces.